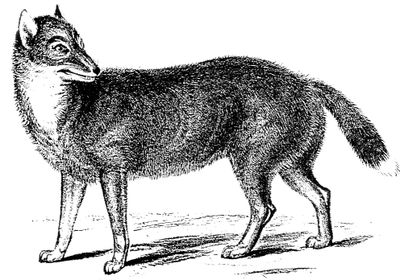

The Warrah

The warrah was the Falklands only native land mammal and for centuries there has been speculation as to how it reached the Islands. Theories included the animals might have arrived on an iceberg or that they might have come to the Islands with humans, perhaps as hunting dogs traveling on canoes with Fuegian Indians. Another suggested that a fleet of Chinese ocean-going junks had visited the Falklands and that the warrah was a descendant of dogs from these ships.

The warrah was the Falklands only native land mammal and for centuries there has been speculation as to how it reached the Islands. Theories included the animals might have arrived on an iceberg or that they might have come to the Islands with humans, perhaps as hunting dogs traveling on canoes with Fuegian Indians. Another suggested that a fleet of Chinese ocean-going junks had visited the Falklands and that the warrah was a descendant of dogs from these ships.

DNA studies published in 2009 showed it was unlikely for the wolf to have arrived in the Falklands through human agency and the authors conclude that they arrived from the continent to the Falkland Islands either through rafting on drifting ice or dispersal over glacial ice during the late Pleistocene period.

Extinction

During his time in the Islands a young Charles Darwin developed an interest in the curious animal, even predicting its extinction in his “Zoology of the Voyage of the Beagle” : “The number of these animals during the past fifty years must have been greatly reduced… and it cannot, I think, be doubted, that as these islands are now being colonized, before the paper is decayed on which this animal has been figured, it will be ranked among those species which have perished from the earth.”

As sheep farming became more established in the Islands and as some believed the warrah had “developed a taste for mutton” a poisoning campaign was undertaken and many were destroyed. By 1870 they were reported almost exterminated with the last one said to have been killed in 1876 at Shallow Bay, West Falkland Islands.

The radiocarbon determination shows that the warrah has been in the Falkland Islands long before first the recorded discovery and settlement by humans.

The Dale Evans Warrah

The remarkable story of the Evans Warrah became even more significant when radiocarbon dating indicated that one of the bones was approximately 1,000 years old – confirming that the warrah predates by centuries the human settlement of the Falkland Islands.

In January 2010, while spending the summer holiday on his family’s farm, local boy Dale Evans (then 13 years old) discovered an interesting bone on the ground. Being a natural history enthusiast since he was just three years old, Dale explored the site further and began to gather up the collection that now bears his name.

The blackened jaw and skull bones that had particularly taken Dale’s attention were sent by the Falklands Museum to the Natural History Museum London for identification and were confirmed as being from a warrah – the “Falklands wolf” – a species that has been extinct for more than 130 years.

Warrah remains are rare, with only six mounted specimens and a small amount of skeletal material known to exist. All these animals were collected by naturalists visiting the Islands during the 18th and 19th centuries. Until this discovery, no warrah remains were held in the Falklands.

The Evans family agreed that the warrah and other remains found by Dale should be held at the Museum where it has been displayed for all to see and appreciate.

Taking guidance from contacts at various British museums and organisations, the Museum & National Trust progressed slowly and carefully. The next step was for to arrange for a further examination of the site. Archaeologists, Dr Robert Philpott and Dr David Barker, who have been carrying out survey work for the M&NT since 1992, were brought to the Islands with the assistance of a grant from the Shackleton Scholarship Fund. The area was thoroughly mapped, and a considerable quantity of material, including more bones and soil samples, were gathered for further examination.

Samples were sent to Beta Analytic Inc., the world’s largest professional radiocarbon dating service. Two samples failed to yield collagen for testing, but the third was successful – the calibrated result giving a 95% probability that the animal died sometime between AD 890 and 1010 (a conventional radiocarbon age of 1100+/-30 BP).

Falkland Islands Museum & National Trust

Historic Dockyard Museum - Stanley - Falkland Islands

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data. Privacy Policy